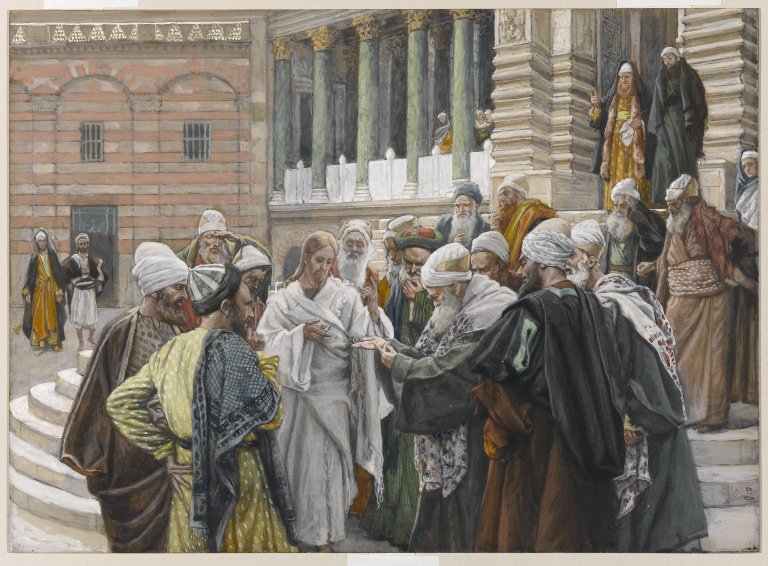

Brooklyn Museum – The Tribute Money – (Le denier de Cesar) – James Tissot, Public Domain via Picryl

On Sunday April 28, I gave the message at our church on the theme of “Discernment in Politics.” It’s been a crazy day and because of that, I do not have a book post prepared so I thought I would share a transcript of the talk. This is not a message about what person or party to support or even how to make those choices. It’s more about living with wisdom and peace in this fraught political season. I hope you find it helpful.

Discernment in Politics: Matthew 22: 15-22

15 Then the Pharisees went out and laid plans to trap him in his words. 16 They sent their disciples to him along with the Herodians. “Teacher,” they said, “we know that you are a man of integrity and that you teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. You aren’t swayed by others, because you pay no attention to who they are. 17 Tell us then, what is your opinion? Is it right to pay the imperial tax[a] to Caesar or not?”

18 But Jesus, knowing their evil intent, said, “You hypocrites, why are you trying to trap me? 19 Show me the coin used for paying the tax.” They brought him a denarius, 20 and he asked them, “Whose image is this? And whose inscription?”

21 “Caesar’s,” they replied.

Then he said to them, “So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.”

22 When they heard this, they were amazed. So they left him and went away. (Matthew 22:15-22, NIV)

Introduction

Have you ever noticed how when you are anxious in anything that it helps to take some deep breaths, to step back, and understand what is going on. Recently, I had a physical exam, and my blood test results show a particular measure out of whack. These days, you often get this info before hearing from your doc. Of course I go on the internet and discover all the dire things this could mean. So I wrote to my doc. It turns out he ran a follow up test that was finer grained, identifying a condition, probably genetic, that was benign, and sent me an educational article. My doc’s discernment and the educational info he sent greatly reduced my anxiety and gave me a few things I could do and watch out for.

Much of our political discourse, particularly in advertising and on social media, is designed to arouse our anxiety. Part of this is to keep us clicking. It appeals to more primitive parts of our brains involved in protecting ourselves, bypassing the parts of our brain that think. There are times when we need that part of our brain. I’d like to suggest politics is not one of them and the example of Jesus in Matthew offers us a lesson in political discernment.

Some Background

A little background might help us in understanding the passage. First of all, it is part of a section from Matthew 21:23 through 22:46 where Jesus is engaging various opponents in the temple during the week before the crucifixion. After responding to a question on what authority he does things like cleanse the temple, he tells three parables about the two sons, about the wicked tenants in the vineyard, and about the wedding banquet where his opponents recognize that he is speaking about them.

So we come to this passage where the Pharisees and Herodians get together to trap him. What’s curious about all this is that they are usually political enemies. The Pharisees are the people’s party while the Herodians support the Roman establishment. The trap they come up with is ingenious. Rome levied a special poll tax on subject peoples that Roman citizens did not need to pay. It was a reminder that they were under the thumb of Rome.

The question they come up with is a “gotcha” question, at least if you just stuck to “yes” or “no.” Answer yes, and Jesus would alienate many Jews who resented the tax, including some of the Pharisees. Answer no, and Jesus could be charged with treason.

When Jesus asks for a coin, they probably gave him a denarius that had an image of Tiberius Caesar on one side. The image alone would be offensive to Jews who were told to “make no graven images” and the inscriptions were equally offensive: “Tiberius Caesar, son of the divine Augustus” on one side and “pontifex maximus” or high priest on the other. Which begs the question of why they have these coins!

So what may we learn from how Jesus handles this?

Jesus discerns their intent. He recognizes they are trying to trap him. Now the intent of our politicians is not always evil, but it is good to listen to the intent behind the words. Another word for this may be interests. Around most political issues there are various interests including our own. The question is whether the interest or intent is merely personal advantage for one group or the common good of all. If a political position advantages some at the expense of others, there is evil or unjust intent.

Jesus discerns ways they are trying to manipulate him. They say some very nice things about his integrity, his teaching, and that he will not be swayed by attention-getting. This can happen through flattery, fear or false promises. There may have even been a temptation for Jesus to be an “influencer.” The invitation to be on the inside, to have influence can be intoxicating. Jesus resists it.

Jesus discerns the false and reductive binary they offer him. So much of our political polarization has to do with turning nearly everything into one of these binaries. Do you know that there was a time in the 1960’s and 1970’s when environmental measures were supported by both parties and a Republican president established the EPA? Then the environment was politicized, and you had to choose between being pro-business and pro-environment, which is like saying, you must choose between walking and chewing gum. And so we are either pro 2nd amendment or for government confiscating all our guns. We are pro-life or pro-choice. We must choose between open borders or building the wall.

The reality is that choosing one side of these binaries excludes the interests and concerns of a lot of people. They also oversimplify the world. Real solutions are often both more complex and creative.

Jesus discerns a kingdom alternative that is far richer. Jesus recognizes the reality that there will always be government. His reply is kind of matter of fact. Give Caesar what is his. Caesar made the coin. The Roman empire is just an earthly power, no less no more.

But he also speaks to what ought to be on the heart of every Jewish listener. What belongs to God? Actually, what doesn’t belong to God? He is Creator. He gives life and land, the cattle on a thousand hills are his, his eye is on the sparrow, he knows the number of hairs on our heads. Sure, let Caesar have his pocket change. And let God have all of your life! Embrace all that is God’s! No wonder people left amazed.

Rather than taking sides, might the role of Christians be to work with both sides, whether locally or nationally to find richer alternatives? One local example I think of is the service of Pastor Rich Nathan on the Columbus Civilian Police Review Board, both supporting the work of police and providing civilian accountability for how they police to restore trust between police and the community.

Jesus discerns ultimate allegiances and our only hope. Any government, nation, or political party are ”just” politics, “just” government. They don’t hold a candle to God’s everlasting global kingdom. They only have a limited function under God. They are not unimportant and we should seek the best people we can find to serve in positions of public trust. But if you are a professing Christian, you have sworn absolute allegiance to the king of kings and lord of lords and there is no part of our lives exempt from that allegiance: our money, our time, our possessions, our sexuality, our ambitions, our work, our retirement, and our politics.

He is also the one we trust absolutely for not only our salvation but for our life and health in the world. I wonder if this is so for us. I wonder if some Christians have embraced the politics of right or left with such a religious fervor because they don’t believe that God can save. They don’t believe the gospel’s power.

I suspect all of us here love our country and all of us may have concerns and anxieties about it. The question is, do we trust God implicitly with that or have we placed an inordinate trust in our politics? If I’m anxious about politics, that is a signal that it is time for some kingdom discernment. Will I trust that God really is in charge, that God will always work for the good of those who love him? Nations rise and fall, and this could even be the trajectory of the United States. I don’t like that idea, and I would work against it happening in my generation, but if it comes, I recognize that my real hope is in the everlasting kingdom of the everlasting God.

Conclusion.

- Discerning intent

- Discerning interest

- Discerning false and simplistic binaries

- Discerning the richer kingdom alternative

- Discerning our ultimate allegiances

These are the things that enable us to live as people of wisdom and peace in our anxious political season. But if you can’t remember all of that, remember the last and pray to always discern your ultimate allegiance. What does God want? What would Jesus do? What has God said in his Word? What does absolute allegiance to Jesus require of me today? For what am I’m anxious that I will trust him, including my anxieties in this political season?

I would suggest two practical tests to help us assess where we are tending toward:

- What are we taking in more? Scripture, good Christian reading or excellent writing in general, sermons and podcasts or Fox or CNN, talk radio, and political memes and posts and arguments on social media.

- What are we talking about more? God and God’s goodness, and the ways we can live our lives loving God and neighbor, or the latest political news, what we don’t like about a candidate or party?

What we are taking in and what we are talking about most reveals where our heart is. I wrestle with this personally. As I turned the calendar to 2024, I recognized what a fraught year is ahead. I challenged myself with regard to these questions with the simple resolution, more Jesus, less politics! Finally, my wife reminded me that one other way we express our absolute trust and know freedom from anxiety is to live joyful and grateful lives for all the good, true, and beautiful things we see and experience each day. That’s another way of saying, “Our God reigns!”